My Trip to the Wright Brothers Memorial and What It Taught Me About Innovation

I visited the Wright Brothers Memorial at Kill Devil Hill in North Carolina, and it felt like wrapping my arms around history. Honestly, without them, I probably wouldn’t even be in the U.S. today. None of us would be casually booking flights across the country or hopping oceans for vacations and business trips.

The Wright Brothers Memorial

Don’t expect lush gardens or picture-perfect scenery. The memorial grounds are pretty flat except for Kill Devil Hill, and that was the point. The Wright Brothers needed steady winds and open dunes to test their flying machine. The most striking feature is the granite memorial tower, perched on top of Kill Devil Hill. A paved path makes for an easy five-minute climb, and once at the top, you’ll have a sweeping view of the entire site.

Inscribed at the base:

“In commemoration of the conquest of the air by the brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright, conceived by genius, achieved by dauntless resolution and unconquerable faith.”

It’s a powerful moment, standing where dreams of flight literally took off.

Next, stroll the wide fields where history was made on December 17, 1903. Stone markers trace the exact distances of the Wrights’ four test flights that day:

First flight: 12 seconds, 120 feet

Final flight: 59 seconds, 852 feet

👉 Fascinating Fact: Just two years earlier, Wilbur nearly gave up, writing, “Not within a thousand years would man ever fly.”

Wright Brothers Monument

Located at the top of Kill Devil Hill, the Wright Brothers Monument pays homage to Wilbur and Orville, their genius and determination in achieving powered flight.

On the fields, you’ll also see replicas of the Wright brothers’ living quarters and workshop shed, built from historic photos. Inside, you can picture their bare-bones camp life while they chased an impossible dream.

Wright brothers’ 1903 camp

Wilbur and Orville Wright lived and worked here during their 1901, 1902, and 1903 testing sessions, late summer through autumn. The reconstructed buildings in front of you depict the Wright brothers’ 1903 camp.

If you know me, you know how much I light up at the success of dreamers. The Wright Brothers Memorial was exactly that. What fascinated me most was how much their family shaped who they became. Their family was the hidden engine behind their courage. Their mother, Susan, grew up tinkering in her father’s workshop and passed that spark straight to her boys. Their father, Bishop Milton Wright, filled their home with books and debate, training them to question limits, argue details, and demand proof. Genius, it turns out, can be nurtured.

Engineering the Impossible

The Wright Brothers benefited immensely from the knowledge and experiences of earlier aviation pioneers, as well as resources available through books and correspondence. They meticulously studied the published research and experiments of Sir George Cayley, Otto Lilienthal, Octave Chanute, and Samuel Langley, often referencing Lilienthal’s data on wing camber and Chanute’s biplane glider designs when constructing their own models.

Otto Lilienthal, the German “flying man,” even published a book in 1889 called Birdflight as the Basis for Aviation. He believed the secret was in mimicking birds, and he strapped himself into gliders with feather-like wings to prove it. His story ended tragically in 1896 after a crash, but that moment drove the Wrights to investigate deeper into stability and control.

Wilbur also requested publications on aeronautics from the Smithsonian Institution, absorbing technical insights from diverse sources and blending these with their practical mechanical experience from the bicycle business. By actively corresponding with experts and adapting existing engineering ideas, the Wright Brothers transformed disparate pieces of flight theory into a unified, workable solution for controlled flight.

Here’s what set Wilbur and Orville apart: they didn’t just dream, they watched. Closely. They studied how birds tipped their wings in the air, and instead of obsessing over engines like everyone else, they locked in on control. That single insight, what they called “wing warping,” became their key. They first tried it on a kite, then applied it to their gliders, and eventually to the Flyer itself. Suddenly, they weren’t just flying, they were steering. Pitch, roll, yaw, the same principles every modern plane still uses.

Wright Flyer (1903 Replica)

Think about that: the Wrights succeeded because they paid attention to the smallest detail.

Why is this relevant?

Because the first flight, and every new innovation since, shares the same DNA.

Innovation isn’t born from playing it safe. The Wrights tested ideas that people laughed at, built their own tools when none existed, failed repeatedly, and kept going. Sound familiar?

Every bold skyscraper, every new workflow, every new idea, we execute in construction carries that same DNA. The process of prototype, test, fail, and refine is the exact cycle we use when we push for better technology, smarter design, and more efficient project delivery.

Change is always called impossible until someone proves it isn’t.

The Wright Brothers gave us more than powered flight. They gave us a blueprint for innovation itself: embrace the empty fields of possibility, mix grit with genius, and risk everything for a breakthrough no one else can see yet.

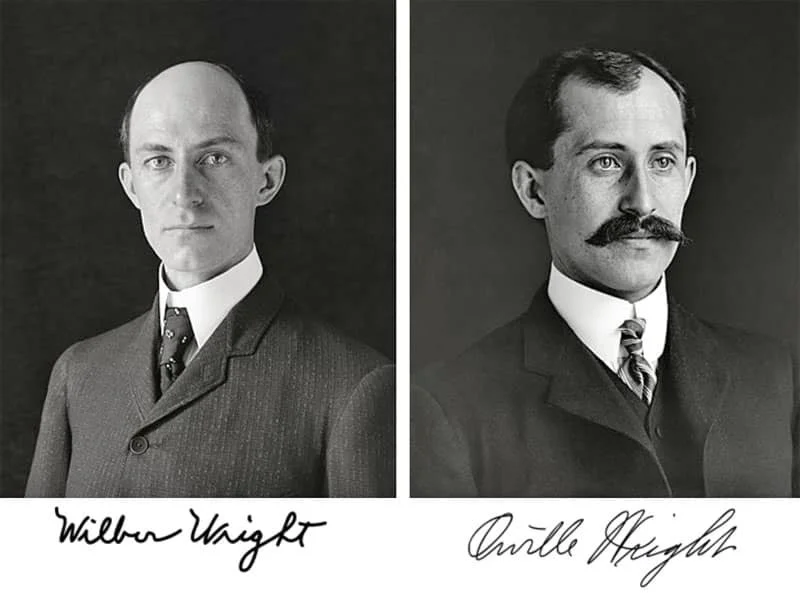

And here’s the irony, the Wrights themselves never looked like the celebrities they became. Reporters described them as quiet, even awkward: Wilbur was thin and studious, while Orville had a mustache and a habit of looking embarrassed. Not exactly the image of global icons. Back home in Dayton, people thought they were half-crazy until Europe hailed them as geniuses. Only then did America recognize what it had in its own backyard.

That’s the part I love most. They weren’t trained engineers. They weren’t wealthy. They weren’t “supposed” to succeed. But they did, with grit, curiosity, and a refusal to quit. Their story remains the ultimate blueprint for anyone bold enough to build something new.