AI at Work: The Silent Decline of Entry-Level Jobs

A working paper titled “Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence” (Brynjolfsson, Chandar, & Chen, 2025) offers the first large-scale empirical evidence on how generative AI is reshaping the labor market. The researchers analyzed millions of U.S. workers’ records from ADP payroll data, a uniquely powerful dataset because it reflects real employment rather than job postings or surveys. They combined this with occupational AI exposure measures and task-level usage data from the Anthropic Economic Index. The authors tracked how employment shifted across age groups, occupations, and AI-exposure levels since late 2022.

The conclusions are sobering.

Fact 1: Employment for young workers has declined in AI-exposed occupations

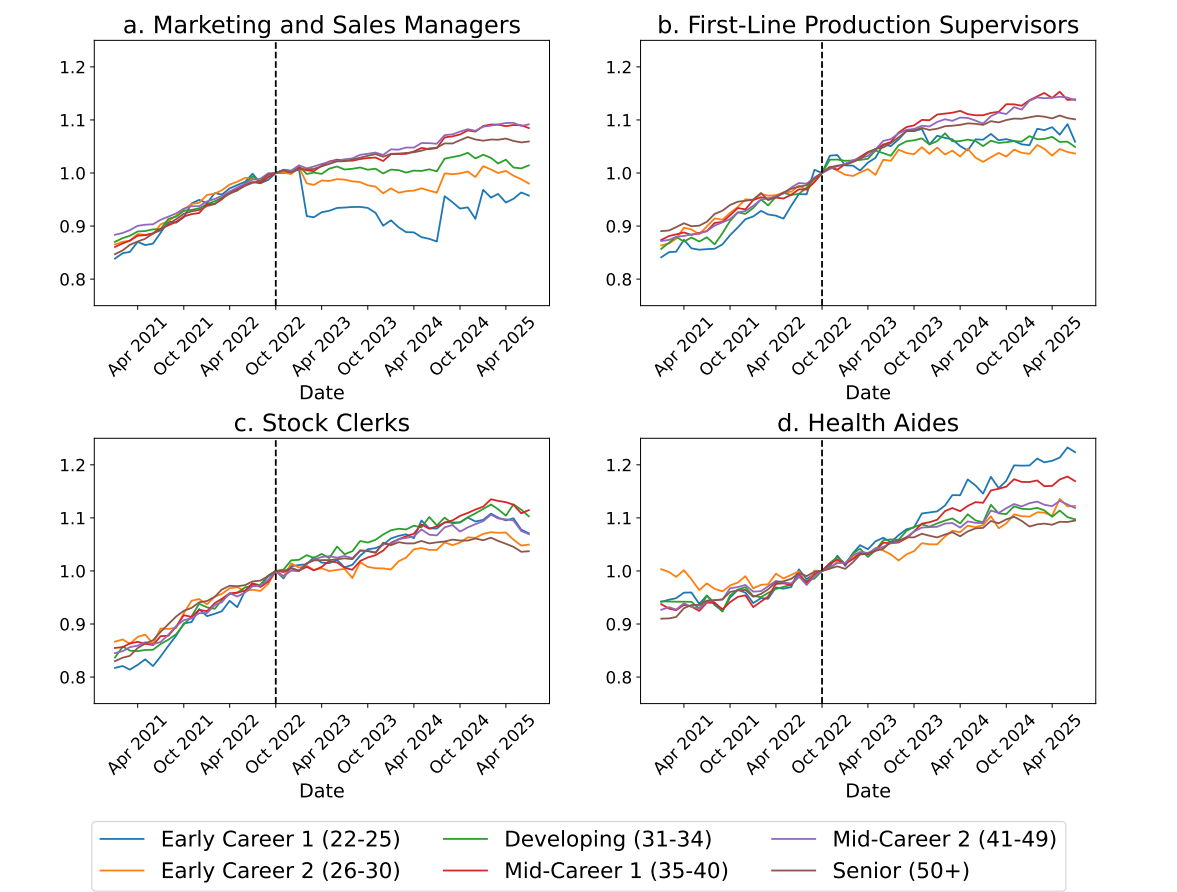

Since October 2022, employment for 22–25-year-olds in highly AI-exposed jobs has dropped by roughly 13% relative to older peers. For example, in software engineering and customer service — two of the most exposed categories — the number of young workers declined even as employment for workers over 35 continued to grow. Marketing and sales managers (quintile 4 exposure) also showed smaller but noticeable declines for younger workers, while frontline supervisors (quintile 3) actually grew, though mostly in the over-35 cohort.

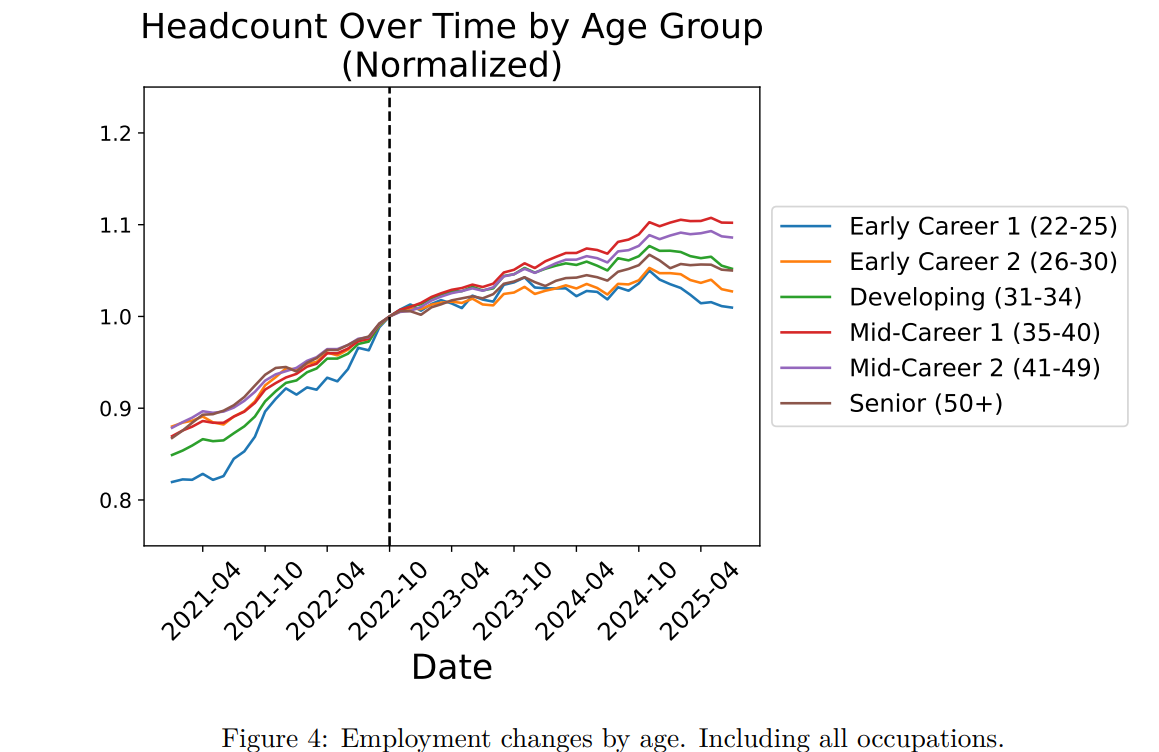

Fact 2: Though overall employment continues to grow, employment growth for young workers in particular has been stagnant.

Nationally, the labor market has remained robust post-pandemic, with unemployment rates near historic lows. Yet when you isolate the data, growth for young workers has clearly leveled off. Figure 4 of the study shows that while employment for ages 30+ continues to rise, workers under 25 are stuck at a plateau. In other words, the big picture looks healthy, but entry-level growth has been stagnant for over a year.

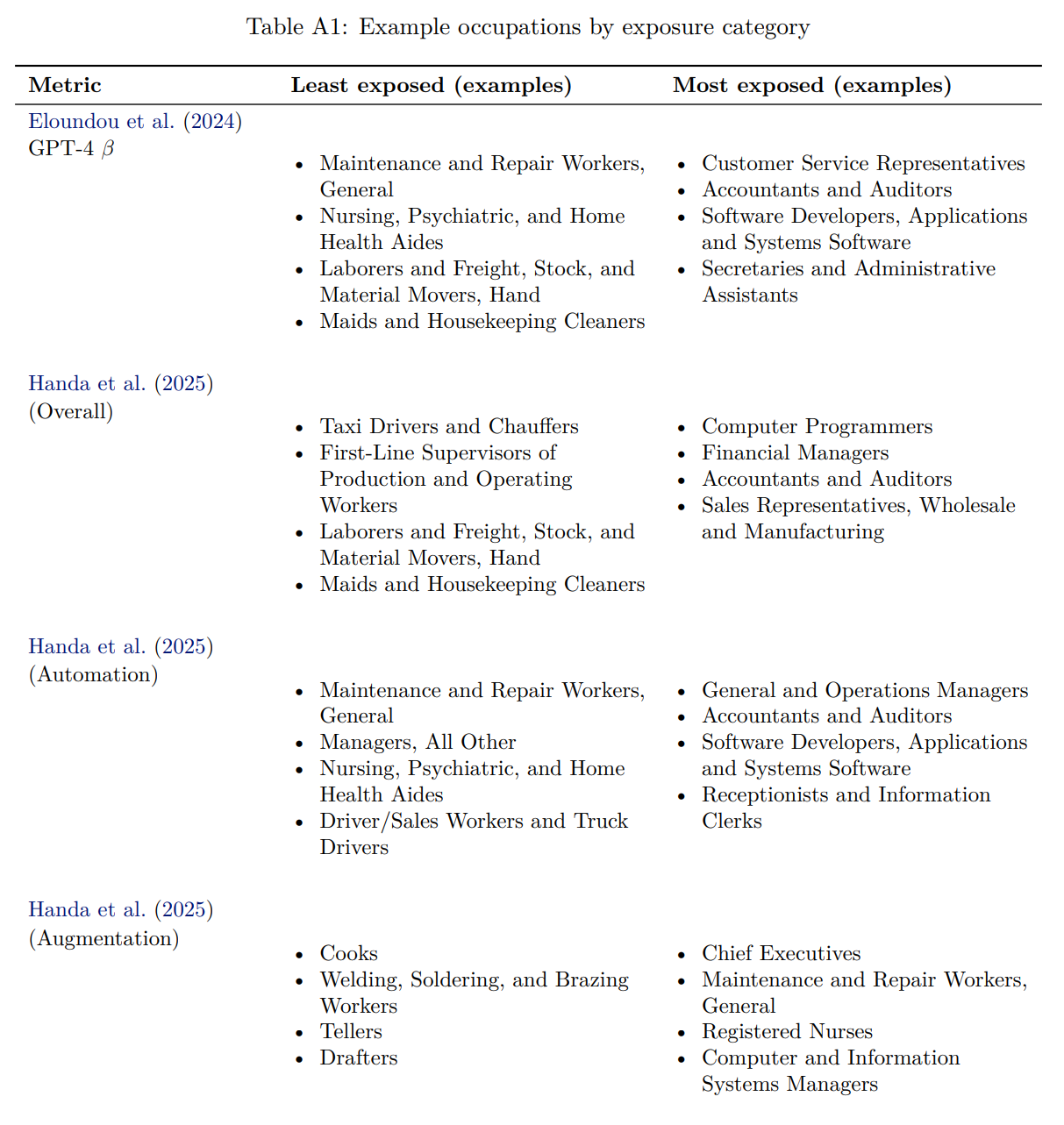

Fact 3: Entry-level employment has declined in applications of AI that automate work, with muted changes for augmentation.

Here’s where the study gets especially clever. The researchers tapped into the Anthropic Economic Index, which tracks how people actually use generative AI tools like Claude. By analyzing millions of real-world queries, they could tell whether AI was being used to replace a task (automation) or to support it (augmentation). The results? Entry-level employment has taken a noticeable hit in occupations where AI is substituting for human effort — think rote, rules-based tasks. But in roles where AI is more of a sidekick than a stand-in, the story looks very different: employment remains stable, with only muted changes for younger workers. In short, when AI acts as a collaborator, it doesn’t crowd humans out — it keeps them in the loop.

Table A1 lists example occupations with the highest and lowest exposure levels for each measure.

Fact 4: Employment declines for young, AI-exposed workers remain after conditioning on firm-time shocks

To test whether these results were simply due to company-level volatility (like a bad quarter at one big employer), the authors added firm-time controls. The decline still held — specifically, a 13% relative employment drop for young workers in the most exposed quintile, even after adjusting for firm-specific shocks. This confirms the trend isn’t random — it’s systemic.

Fact 5: Labor market adjustments are visible in employment more than compensation.

Despite the employment squeeze, wages have stayed steady. Compensation for exposed roles hasn’t fallen significantly; instead, firms appear to be managing risk by slowing or halting new entry-level hires. For young professionals, that means the bottleneck is not in how much you’ll earn if hired — it’s in whether you get hired at all.

Fact 6: Findings are largely consistent under alternative sample constructions

While software engineers and customer service reps are the clearest examples, the study shows similar dynamics in other fields. Health aides (quintile 1–2, low exposure) actually saw faster job growth for young workers than for older ones, highlighting how AI disruption is uneven. But the consistent thread across all six facts is that exposure to AI matters more than industry labels — and even occupations outside Silicon Valley are beginning to feel the shift.

Why should industries outside software engineering care?

Because entry-level jobs are more than labor inputs — they’re crucibles of learning. They’re where codified knowledge turns into lived expertise, where mentorship happens, and where the next generation of leaders is shaped. If those opportunities erode, the ripple effects are profound: a thinner talent pipeline, slower skill development, and ultimately a workforce less resilient to shocks. This isn’t the first time technology has reorganized the economy. The IT revolution displaced clerks and typists before creating entirely new categories of digital work. The current AI wave will likely follow the same arc — disruption, reallocation, then reinvention. But the interim period can be bruising, especially for young professionals standing on the lowest rung of the career ladder.

So, where does this leave the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) industry?

On the surface, relatively insulated. Construction workflows are physical, tacit, and context-rich. Pouring concrete, sequencing trades, or resolving constructability conflicts is not something a large language model can master overnight.

But at the entry-level layer, risks abound. Many of the tasks traditionally handed to interns, junior engineers, or first-year estimators — think quantity takeoffs, specifications writing, drafting technical details that repeat across projects, code compliance checks, baseline schedule prep, change order documentation, or RFI and submittal tracking — are highly codifiable. These are precisely the activities most susceptible to AI-driven automation.

The opportunity, however, is equally striking. If AEC firms embrace AI as augmentation rather than replacement:

Repetitive calculations vanish.

Young professionals shift faster into interpretation, judgment, and stakeholder communication.

Firms can reimagine entry-level roles as “AI-assisted apprenticeships” — where the learning curve is accelerated, not cut off.

If you’re 22–25 and entering a field that’s flirting with automation, here’s how to stay ahead:

Master the tools. Don’t resist AI; learn it.

Double down on tacit knowledge. Spend time in the field. Walk jobsites. Ask questions. These are the insights AI cannot replicate.

Move from execution to interpretation. AI can draft the baseline; your edge is knowing what it means for cost, risk, and schedule.

Stay adaptable. Career paths will be nonlinear. Hybrid roles — data + construction, design + finance, operations + analytics — will define the next decade.

The Stanford study doesn’t forecast a dystopia. It sketches the early contours of transition. For AEC, the warning is not about mass layoffs but about how we structure entry-level work. Will AI hollow it out? Or will we use it to accelerate the path from apprentice to decision-maker?