Why Don’t Robots Feel “Normal” on Construction Sites? (Yet)

I was reading a research paper from NVIDIA research this past weekend—yes, a robotics paper, and yes, voluntarily—and I came across a concept that stuck with me: social navigation in robotics.

Now, before you mentally check out because "robots are still too far-fetched for construction," hold on. I get it. Most of us don’t associate social intelligence with construction tech. We imagine robots as tools for factories or Amazon warehouses, not as part of our jobsite crews.

But here’s the thing: robotics in construction is no longer just a theoretical idea. We already have machines like Spot by Boston Dynamics showing up on jobsites. Some of you have probably seen them walk around, snapping site photos or scanning progress. We’re seeing real investment and real deployment across the industry.

And yet... something still feels off.

Despite how useful they are, robots like Spot often seem like outsiders. They move through space but don’t quite belong in it. They complete tasks, but don’t understand what’s happening around them. And honestly? That’s a problem.

It’s not a hardware issue. It’s not even a data issue.

It’s a people issue.

Humans are naturally empathetic and imaginative. We don’t just complete tasks—we observe, interpret, and adjust. We wait for someone else to talk. We make space for others in crowded hallways. We understand subtle social cues that make our movements feel respectful, coordinated, and safe.

Robots don’t do any of that.

They’re fast, efficient, and focused—but socially? They're clueless. And that’s where NVIDIA’s research caught my attention. Instead of focusing only on speed or stability, they’re exploring how robots can behave in ways that feel more human-aware by building systems that understand context, communicate intent, and move through shared spaces with a sense of politeness.

It’s called social navigation, and once I started reading about it, everything clicked.

Because maybe the reason we don’t trust robots on construction sites yet isn’t because they’re not capable—but because they don’t know how to behave.

So what does social navigation actually mean?

The 8 Principles of Social Navigation

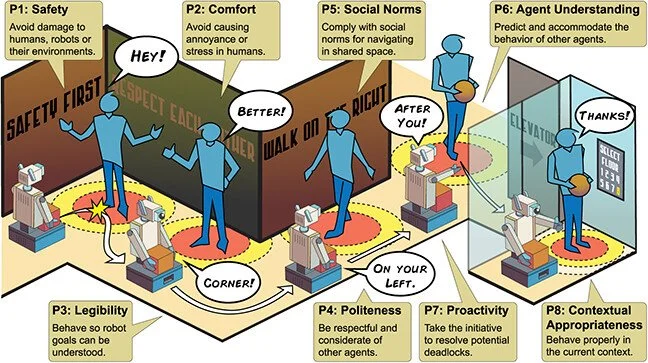

The researchers define a socially navigating robot as one that completes its tasks while also improving or at least not degrading the experience of other agents—humans or machines—around it. Social Navigation Robot.

They propose eight core principles to guide how robots should behave in shared environments:

Safety – First, do no harm. Robots should not injure people, other robots, or damage their surroundings.

Comfort – Humans should feel at ease. No sudden moves, no buzzing too close.

Legibility – Make your intentions clear. If you're passing on the left, move like you mean it.

Politeness – Don’t cut people off or push through crowds like an impatient New Yorker. Even a robotic “excuse me” goes a long way.

Social Competency – Understand and follow social norms. The robot equivalent of “don’t be weird.”

Understanding Other Agents – Predict human actions. Are two people talking? Maybe don’t walk right between them.

Proactivity – Don’t just react—anticipate and prevent problems. Think crowd flow management, not chaos avoidance.

Contextual Awareness – Know where you are. What counts as “polite” in a hospital is different from a construction site.

These principles are more than just moral guidelines—they’re optimization goals. In AI terms, you can actually code these behaviors into the robot’s decision-making engine. It’s not just “go from A to B.” It’s “go from A to B in a way that doesn’t annoy people, cause danger, or make humans think you’re a jerk.”

The paper also dives deep into how to measure these traits, simulate them in virtual environments, and benchmark improvements—so this isn’t just theory. It’s a roadmap for how we might teach machines to be good co-workers.

Let’s refocus on our Construction robot - Spot, the four-legged robot developed by Boston Dynamics.

If you haven’t met Spot yet, picture this: a yellow robot dog (yes, dog) that walks on four legs, climbs stairs, navigates rough terrain, and carries a camera payload on its back. It doesn’t bark, but it does scan, capture, and map. Spot has been deployed on hundreds of jobsites across the U.S.—collecting progress photos, scanning environments, and sometimes just turning heads.

At first glance, Spot feels like a novelty. People pull out their phones. They wave at it like it’s a mascot. But underneath that playful vibe is some seriously advanced robotics: Spot is mobile, autonomous (to a degree), and fully programmable through Boston Dynamics’ software development kit (SDK). Contractors use it for 360° image capture, laser scanning, safety inspections, and more.

But the question is - is Spot socially intelligent?

The good news is, it can be, because Boston Dynamics built Spot to be highly programmable. Its SDK allows developers to define behavior trees, retrieve robot state, stream from cameras, create custom motion commands, and even link Spot to large language models like ChatGPT for conversational experiences. But that’s the point: if you want Spot to act polite, you have to program it to be. There’s no “social behavior mode” you can turn on. There's no default package for manners.

Here’s where it gets real.

Construction isn’t just about finishing the job—it’s about how teams work together under pressure, in tight quarters, across disciplines. Spatial awareness, communication, body language, and trust are everything on a jobsite.

So if a robot doesn’t understand the social rhythm of the site—even if it’s technically efficient—it creates friction.

It becomes something people work around, not with.

So, what do you think?

Would a more “social” Spot feel like less of a guest and more of a crew member?

Do we need robots to be polite, or are we just humanizing tools that don’t need it?

Curious where you land. Drop your take—I’m all ears.